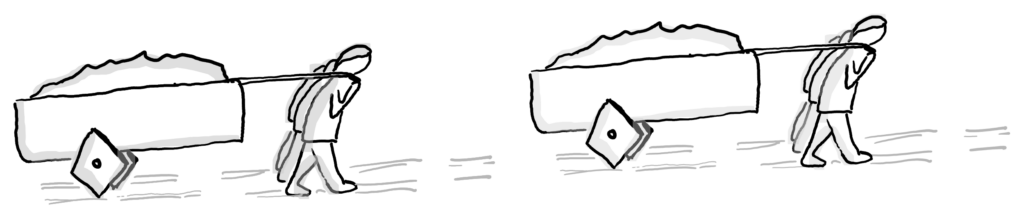

Getting a performant team needs an investment into the team. Instead of frantically or stoically pulling a cart with square wheels, a team should be able to spot the fault in the system and change. This however proves difficult in practices. The good news is: collaboration creates the team and thus providing room for collaboration is an easy way to nurture the team.

Different situations require different teams

The term team is far from clear and agreed. You might even use several different definitions of team without realizing it. But a football team has completely different setup and dynamics than a software team. This is totally reasonable: different task, different type of team. However, when forming a team, people are not aware that their notion of how people work best in a team comes from a different situation and does not fit well with task and situation at hand. Here are three prototypical teams.

Workflow teams: In administration, similar to an assembly line in manufacturing, requests are handed over from one “station” to the next, every station adding their bit to fulfilling a request. Cleverly designed and agreed workflows hold everything together. Teams gather employees working at one station. These teams handle things like allocating requests, planning vacations, optimizing output, ensuring quality, providing a social space, introducing new employees and more. However, the bulk of their working time employees spend at their station doing their individually assigned tasks. These task are mostly routine work that follow well defined rules, only few require problem solving and this problem solving is usually restricted to the narrow scope of the station. Workflows efficiently coordinate what individuals do.

Squads: To e.g. extinguish a blazing fire, several persons need to make a joint effort. In these dangerous and time-critical situations, a command structure has been a successful pattern. Decisions are taken in minutes or even seconds and everybody in the squad can act immediately in a coordinated way. Of course only, if there is accurate and clear communication within the squad. Through training, the members of the squad learn how this cooperation works and to rely on the others. In such a model, the squad members efficiently cooperate and can thus master highly dangerous situations.

Super-brains: When creating innovative and complex products, several persons need to combine their different expertise (see Know how to shape the future): “put a bunch of persons in a room and let them figure it out”. Team members form a super brain where thoughts and ideas from one person inspire others, different perspectives combine, new knowledge is uncovered and from individual pieces are a comprehensive solution emerges. Through such collaboration, super-brains can solve problems no individual would be able to.

The software teams you might encounter in the real world usually combine elements from all of these three prototypical forms. The result are interdisciplinary teams, i.e. teams where individuals with different backgrounds combine their expertise and energy. Such teams use different working styles flexibly and for different purposes:

- individual working: team members individually do a task. Routine work and simple tasks can be easily done individually. Individuals can focus their effort and become very efficient.

- cooperative working: team members break up one task in several sub-tasks and work individually on the subtask. They coordinate who does what by when and thusly optimize team output. Cooperative working is well suited for basically simple tasks that need many hands to complete in a short time. Stand-up meetings like the daily in Scrum are very well suited to coordinate such work.

- collaborative working: several team members combine their brain power to complete one task together. Collaborative working is especially helpful for complex problem solving: the super-brain of a strong team can solve more complex problems than individuals could.

Strong teams exhibit strong team properties

When individuals interact, an entity, a “We”, starts to emerge. It sets these individuals apart from the rest of the world. While at the beginning, such a “We” might be frail, it can grow and even dominate the individuals it is composed of. When such a “We” has reached some quality, people will call it team.

Note: What level of quality distinguishes a team from not a team is not well defined. For example, it is generally agreed that a team should have a shared goal. Something the individuals try to achieve together. Still, at any time the individuals in the team will have their personal goals as well, things they want or have to achieve. For some individuals, a team goal just gives a frame, a directional drift, a field to pursue individual goals. Others set their personal goals aside to focus, for now, on the shared goals. Yet others adopt the team goals as their own goals, replacing former goals. Given any team, expect quite a mix!

A shared goal is just one of the properties a “We” can exhibit. For the sake of simplicity, I clustered the many different properties into the following ones:

- Team story: Shared purpose, common goals and an agreed approach gives teamwork a clear direction and a sense of purpose. In a strong team, team members identify strongly with the team story.

- Team know how: A shared language of the why, what and how; understanding of the others, their skills, perspective, motives and reactions; and a balanced set of skills, suitable for the task ahead: In a strong team, the individuals are well attuned to each other and form a super-brain that achieves much more than the individuals would ever be capable of.

- Team culture: A shared set of values, principles and behaviors guides the individuals activities and especially provides a shield in case of stress, conflict or crisis. A strong team rewards interaction, learning, respect, trust, and helping each other.

- Team spirit: The current mood of a team drives the individual motivations and bonds the individuals together. A strong team has a healthy and motivating spirit.

- Team processes: A shared set of roles, responsibilities and work procedures allow a team to efficiently work together. A strong team constantly adapts roles, structure and processes to the changing circumstances and to the needs of the individuals in the team.

Developing team properties

To develop team properties, teams have a couple of different levers. They will need a good combination of them all.

Set the frame for collaboration: Team properties emerge first of all through collaboration, i.e. when the members together achieve something great for their users and customers. In fact, the closer the team members collaborate, the more they elaborate the team properties. As soon as they start working individually, the team properties wane down.

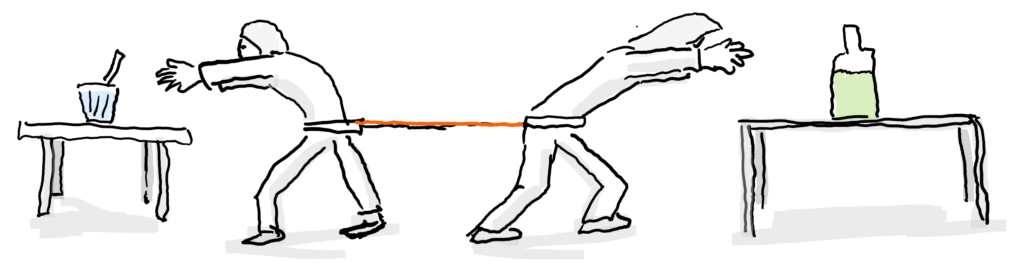

Collaboration is especially critical when taking decisions. Who should a team involve? Fewer persons can result in faster decisions. The potentially fastest version is a strong leader who decides. Increasing the number of persons creates a better understanding and generally leads to higher acceptance of the decision taken. A team can negotiate how it decides. An interesting tool is delegation poker (see https://management30.com/blog/delegation-poker-gamification/). The idea: you discuss with the team on how a decision will be taken. The options vary from a dictatorial approach (e.g. software architect or a product owner decides and tells) to full democracy (i.e. discussed until consensus is reached).

A team could do the following:

- Define meetings where the whole team can work on the big decisions. The team members are then well aligned and can quickly do it.

- Create a team space with loads of walls, whiteboards etc. where team members naturally interact with each other. Use a team wall, even for individual work, so that conceptual work becomes visible to the whole team.

- Omit letting somebody specify a solution and someone else implement it.

- Create collaboration points while a story is implemented, e.g. by pair or even mob programming, quick story reviews, stand-up presentations and more.

- Split up work once the team has become proficient so the team can deliver more.

- Let team members discuss their decisions and designs with others, thus implement some good practices like code reviews, dev exchanges etc.

- Setup processes so that team members get first hand feedback from those who really matter (you would expect this to be customers and users and of course some VIPs).

Invest into the team: To set collaboration, team members need to discuss, goals, values, ways to achieve the goals and more. Explicitly investing into team properties seems like a great idea to me. You could:

- Run regular inspect and adapt meetings, aka retrospectives in Scrum and manage the improvements.

- Setup team workshops where the team can have an in-depth discussion about roles, processes, values, their needs and expectations etc. and discuss more fundamental changes. You might do this regularly with the team.

- Let the team experience other ways of working to reflect on how they work and what they can improve.

- Don’t forget social events, coffee breaks, lunches and all the other activities that bring people closer together and provide a social space.

Work with the individuals in the team: We as individual differ highly in our skills, needs and behaviors. For a team to work well, some social and communication skills are required and some behavior is better suited than others. Thus you can for example:

- Provide education and coaching around conflict management, workshop facilitation, and more

- Work with the individual and help them to develop the skills needed to collaborate better.

- Listen to individuals in the team, their needs, career wishes and problems and discuss with them options within – or outside of – the team.

Work with the context: Things happening around a team strongly impact the team. For example: decisions from management can swing the mood in a team, i.e. the team spirit, from one extreme to another; a tightly fixed Bermuda triangle (budget, time and scope) usually causes stress and heats up conflicts; strong personal incentives and career goals for team members push individual goals over team goals; the list could be continued.

Some of these issues can be resolved by the team or at least escalated to someone who can resolve them. For others, the team could at least decide on a common position. Here, teams profit from strong personalities in roles like product owner or system architect: Such persons have been empowered by the organization to decide and should be respected when promoting the position taken by the team.

Team structure and three archetypes

Teams will create some internal structure. They create hierarchy, assign roles, responsibilities and decision power. There are obviously different of structuring teams and whatever way a team chooses will have positive and negative impact on the teams performance. There are three archetypes teams combine into their specific mix:

Workflow structure: Teams with a strong workflow structure define a process and hand over items from one person to the next, following the work flow. In a agile team, the usual implementation is to create sub-teams along the different types of tasks around a backlog item: those who identify user stories and order backlogs, those who ready them for development, those who develop them, those who test them, those who validate them, and more. Each sub-team takes the user stories from their inbox, matures them and hands them over to the next team once done.

Command structure: Teams with a strong command structure assign one superhero – aka single wringable neck – who solves the problem of what the best thing to do is and delegates sub-tasks and the execution to the team members. The superhero shapes the product and takes all the major decisions. In most cases, such a super hero cannot cover all skill areas (see Know how to shape the future) and thus chooses one or two side-kicks to complement.

Super-brain structure: Teams with a strong super-brain structure combine the individual expertise . The more difficult a problem is and the more far-reaching a decision, the more likely the whole team is involved in taking it. For this, team members form a super-brain, where ideas and insights flow freely in the team and combine to solutions, none of the individuals would have been able to detect. Such teams also split up work and change between the afore mentioned co-creation sessions and individual execution. Individually or in small sub-groups, they run stakeholder workshops, conduct user tests, prepare UI wireframes, do technical mock-ups, write code, improve development environment and more.

Todays agile software teams usually mix workflow, command and super-brain structure. A typical setup – not the best per se, however – is the following:

- Product owners quite define the functions to be implemented and the order of implementation. They thusly establish a command structure for the what and what for.

- In some teams, software architects create key concepts and decide on the technical solution. This is in fact a second command structure, this time for the how.

- In other teams, the developers team up for the difficult concepts and thus follow more a super-brain approach for the how.

- When specialists join the team (especially designers, business analysts and testers), these are usually structured along a workflow.

Most teams create such a mixture not by careful thought. Usually, it’s just the result of what team members did so far and how a company works in general. It’s just the easy way of doing it, and not necessarily the most effective one. It is probably worthwhile to ponder a bit more on how the three archetypes influences how team members behave, think, work and how this impacts team performance.

team know how and learning

Software development is still a complex task that requires know how in many fields of expertise: about customers, users, markets, business opportunities, technology, internal processes and more. No software project is the same and acquiring know how is daily business. In addition, many people in product development are eager to learn and grow. They need opportunities to do so.

The workflow structure allows the sub-teams to focus on a clear set of task, optimize their work, and become highly performant in their area. It creates specialists and team members grow mainly in their field of expertise.

In the command structure, the superhero pulls all the string and the knowledge is concentrated on this person. Others have difficulty to grow and expand their skills, unless the superhero actively pushes them into the learning seat. In this case of course, the potential is great: having the strong super hero behind to put them back on their feet when they fall, they can learn and experiment.

In the collaborative structure, team members work closely together, juggle ideas and participate in tasks from other fields of expertise. Team members gain a much broader view and set of skills, know each other very well and grow in many ways.

decision making and problem solving

Taking good decisions quickly boosts team performance. This challenging team process needs creativity, clever problem solving strategies, effective feedback loops and more.

In the workflow team, each sub-team decides for themselves based on the information available and their assumptions about later work. E.g. business analysts work out processes and what functions they need, the architects work out the best architecture and so forth. This isolated decision making simplifies the problem and is thus fast. It however finds solutions that are great from one perspective and poor from others. It also creates friction as the team members pull in different directions.

In the command structure, the superhero with vast knowledge takes the key decisions with or without consulting others in the team. Expect fast decisions that respect many aspects. However, if such a powerful superhero lacks essentials skills and cannot spot this gap, the solution will have major flaws. Tasks that need a great amount of creativity profit from several brains inspiring each other – another limitation for superheroes. In addition, the others in the team have difficulty taking the few remaining decisions and thus the superhero needs to verify smallest details and clean up.

In the collaboration oriented approach, the team as a whole defines together, who should be involved to what degree and thus looks at a problem as holistically as is needed. This promises sound decisions where almost all aspects are reflected. However, if not paying attention, having to synchronize the many persons can create bureaucratic processes.

Conflict resolution and social skills

Conflicts, i.e. disagreements between those involved in the development, are as normal as breathing. However some conflicts are not resolved and seriously hamper a team. Especially when the pressure is high, conflicts are a key contributing factor to stress and even burn-out. For a team it is crucial to detect and work on the conflicts.

The collaboration oriented approach demands much from a team and its members. Strong personalities with diverging viewpoints cause ample fuel for heated battles and evil schemes. Having to agree on one solution is the perfect arena for the conflicts. It may need help from a neutral and external mediator. On the other hand, many conflicts get apparent very quickly and the team members can and have to grow their social skills. In the long run, with a little support maybe, team members learn how to deal with conflict in a constructive way and even thrive on different ideas to find even better solutions.

In a workflow oriented team, sub-teams are much smaller and thus clashes between personalities are less frequent. As the workflow separates the sub-teams from each other, conflicts generally remain cooler and can be covered up. However, what started with the social game of blaming and shaming results over time and with a bit of pressure into serious personal issues. Instead of a ‘We’ for the whole team there is a ‘we’ for each sub-group who needs to make sure the customers get a decent solution even though the others – pinheads as they are – have no clue what they are actually doing. As conflicts do no become easily apparent until very late, teams working with a workflow structure need to be extra vigilant. Introduce frequent exchanges between the groups so they understand each others challenges!

In the command structure, the superhero gets the fame and the blame and is right at the heart of almost every conflict. Much depends on the leadership and social skills of the superhero. If this person is not able to resolve conflicts, they will heat up to melting temperature and if team members do not fit, they sooner or later quit.

Balancing work and bottlenecks

Ideally, every person has just the right amount, variety and difficulty of tasks ahead. They can fit in some socializing with colleagues and have some slack time to learn and innovate. Basically, companies are well advices to create a healthy work environment where people can grow. Such an idealistic situation obviously never exists. However the structure a team chooses can quite impact the load on specific persons.

The workflow structure is based on the principle of an assembly line. Stations in an assembly line produce at a constant speed, each item takes the same amount of time at each station. Therefore the whole assembly line can be laid out in an optimal way. In software development, this is not the case. Some stories take month to ready for development and five minutes to implement, others just the other way around. This lack of constant speed causes flow issues. The persons in the sub-teams are either overloaded or waiting, both lead to some unhealthy choices:

- A waiting station invents work, complains about the lack of work, does work that is currently unimportant or takes over a second project to fill the gaps. While the first actions put the stress on the currently overloaded station (it adds more work), the last option returns like boomerang, as soon as the waiting station gets more work.

- An overloaded station will try to speed up work by adding more people, by hurrying up, by taking short cuts, blaming others and similar strategies. All of them usually increase the pressure on the overloaded station.

With a well design workflow structure and a bit of pressure, it is easy to push one person of the team into the hot spot and let this person slowly burn-out. You can find an example recipe here: UX in a burn-out system.

In the command structure, the superhero takes most of the many big and small decisions. The superhero is very likely flooded with work, while others either wait for a decision or take a bad decision the superhero has to correct later. In addition, as most of the task are assigned by the superhero, the team members stop working once their task is complete and ask the superhero for the next task.

In a collaborative approach, team members can help each other out and take over tasks from another persons field of expertise. This allows the specialists in a team, e.g. a software architect, a designer, the math or physics guru, to hand-over some of the tasks to others when overloaded and helping others when not enough work is available. The team can balance the workload of specialists and those specialists can concentrate on the real challenges. However, some people are very happy to focus solely on their field of expertise and leave the rest to others. The more such people are in the team, the less the collaborative approach is going to work.

Under pressure

Pressure is a constant issue as the wish list is usually much bigger than what can be done. Pressure is a again a key element to create inefficient teams. The different team structures now respond differently to pressure.

In a workflow structure, the sub-teams usually increase their through-put and optimize their local processes. They drop things that complicate their lives, like working together and thinking for those coming after them. Expect a lot of blaming, shaming and generally friction.

With a command structure, the pressure is high on the superhero and this person’s behavior and genius decides whether they find the Columbus’s egg or whether the weakest persons in the team burn-out.

The super-brain emerging from the collaborative structure could actually find very simple solutions and thus reduce pressure. A strong team is also more powerful and can more easily repel pressure. A weak team will break however rather break apart into individuals who feed each other to the lions. In addition, strong managers outside of the team can drastically weaken a team.

Information flow

The solution a team strives for usually changes drastically as soon as team members experience how users go about their work and what customers and other stakeholders need. Direct contact between team members and stakeholders is in most cases the best approach. Every person in between will filter, summarize and translate – information is lost and distorted. The setup in a company can make it quite difficult to get access to specific stakeholders (especially company external ones). Thus establishing and keeping contact with stakeholders can become a significant task for the team. The structure of the team can add to these difficulties.

The workflow structure fosters information loss and distortion: Only few persons (product owners, business analysts and maybe designers) can get in contact with stakeholders. The sub-teams work quite isolated, pass the result of their work onwards with at best some heavily digested information about users and stakeholders. It needs extra effort from the team to enable first hand experience.

In the command structure, the superhero is in the hub of the information flow and keeps the closest contact with the stakeholders. Information piles up on the superhero’s desk. Communicating it onwards consumes valuable time. Thus the superhero knows almost everything, all the others have difficulty to get to the needed information in any other way than asking the superhero.

In the collaboration structure, everyone in the team can be in contact and gain first hand experience – alas, everyone a different one. Aligning the gained experience is the challenge here. For this, different disciplines came up with solutions, like stakeholder maps, personas, user journeys, feedback boards and more. They integrate and consolidate collected information. It is more that the team uses such tools and takes the time to continuously update the results.

Shared goals:

not my job, not my goal –> redefinition of goals –> no shared goal?

The resulting solution

In an assembly line, the complexity is not in the daily execution and to produce the , but in setting up the assembly line to optimize throughput. The workflow structure takes this assembly line metaphor into services and also software development. In software development, the complexity now lies

Quality of the solution: Every solution is a trade-off between what users and business needs and technology can deliver. Ideally, simple solutions from a technical and business perspectives should meet relevant needs.

In a workflow structure, due to local optimization, information distortion and friction, the solution likely is overly complicated, not well fit for purpose, expensive to build and maintain. Some project will fail completely. Workflow teams ca, it depends on the complexity of the problem and.

In the command structure, solutions can be fantastic or be a total failure with major flaws, it just depends on the superhero.

The collaboration structure can enable teams to provide very simple and powerful solutions that provide exactly what is needed. The challenge lies in team dynamics and the conflicts between team members. A team might take a lot of time to reach an acceptable compromise. Solutions range from fantastic to total failure, depending on how strong the team is.

[Image stakeholder – team interaction]

- loss of empathy and understanding of the position of others.

However, there are a couple of challenges go overcome

- knowhow and skills –> more complex team structure

- time to market –> parallel work

- not enough devs –> add non-devs to the team

- conflicts –> facilitator needed

What we talk about and what we should talk about (FHSG Slide)

How to efficiently kill team work

As may have become quite obvious, there are many many really efficient options to hamper teamwork and make teams basically ineffective. Coming up now: some very popular ones.

Most companies tend to demand too much and induce the Team disorder: Featuritis. The team tries to quickly deliver the visible stuff and delays quality, architecture, team, individual growth, and organizational impact to later, i.e. never. This is the ideal soil for a burn-out machine and it scales to the company level as teams look for themselves, do not communicate well enough and define products and timelines that do not fit together. Agile Frameworks like SAFe try to solve this problem by introducing a system of backlogs and synchronizing teams.

Some sophisticated reward systems create high incentives for individuals. Such a system needs an assessment of the individual performance of a person. However, in a strong team, the individual performance is highly dependent on the team performance and the opportunities available in the team. A strong incentive will usually make persons work for themselves and against the team and the others in a team.

A frequent strategy is to assemble teams with loads of specialists. They represent their discipline in a the team and are only partially working for the team. Everyone has more than one and different bosses and is mostly focused on their contribution rather than the overall success. Information flow, balancing work load and problem solving gets highly challenges. The juggling of multiple bosses fosters an opportunistic working style: Whoever shouts the loudest gets the most attention.

Unspoken requirements for teams

Interdisciplinary teams are generally established to solve a complex problem. However, the organization expects the team to achieve other things as well – sometimes without ever mentioning it and sometimes even without being aware or it:

Individual growth: While working in a team, the team members develop their skills, acquire know how, refine their personalities – they grow. A team can and should provide opportunities for the team members to grow. Therefore, a couple of things need to take place:

- A discussion within the team about personal growth: What individuals strive for and what can be made possible in this team.

- Creating opportunities for people to grow. E.g. rather than assigning a task or a responsibility to the most skilled person, find ways to assign it to those who want to grow into it.

Social space: Most humans can only thrive in a good social space. Teams are very important social spaces when it comes to our work environment. However, social spaces go beyond a strictly professional relationship. Teams should become a place where team members are welcomed and valued. Teams should make room

- for building up trust, learning and helping each other.

- to share personal moments and feelings and to create fond memories of shared moments within the team.

- to turn conflicts within the team into a win for the team.

- to discuss how the individuals can and should contribute to this social space.

Organizational impact: When thinking about change in organizations, one thinks about the big reorganizations, the highly visible tipping points of change. There however is a lot change happing all the time. Teams are and should be making such change happen. Therefore they need to become active and e.g.

- interact with others to share insights and know how.

- align goals and improve collaboration with those around the team.

- use and especially contribute to company assets, so more can profit.

Reviewing such expectations sheds some light on the difficulty a person faces who takes on a leading role in a team. This is just too much for most! Especially if team members just care for their own job. Developing complex products needs persons who act responsibly. Leading is about enabling them to do so.

Taking responsibility

When feeling responsible for something, we take care of it and also feel accountable for what we achieve. Feeling responsible takes us beyond just doing an assigned job. It will make us think and act for the good of the person or thing we’re caring for. As we are acting beyond job specification, we judge our actions and achievements against a set of principles and values from a guiding authority like religion, morals, science, laws, aesthetics and more.

If people are consistently able to take responsibility and achieve results up to their and other standards they can take control, gain confidence, grow and become more resilient in difficult situations. Others can trust them and this strengthens their relationships. It also changes how the members of a team can work together. When the team members take responsibility for their tasks and for what the team tries to achieve together, this creates a more productive environment. At least, in an ideal situation.

However, just designating someone responsible does not imply that this person will feel responsible. We also develop a feeling of responsibility for something that we were never asked to. We even go as far as to redefine our job so it matches what we feel responsible for. We are bound to invest much more energy into what we feel responsible for than for other things. We have to interact with others and they only grant us limited responsibility. They restrict the actions available to us and evaluate our achievements against their standards.

As you might have already spotted, there is a huge potential for conflict in this system of responsibility. See UX in a burn-out system: at the heart of this conflict is one person who is taking responsibility for UX against all others in the team! You have probably seen many other difficult situations, like someone feeling responsible for something but the bosses rewarding the opposite? Or the person lacks options and skills to achieve a “good” result?

Taking responsibility can be everything from highly rewarding to burning out. Here summarized the crucial elements to consider:

- The person’s willingness to take responsibility;

- rewards for taking responsibility;

- a safety net in case of a perceived failure;

- good amount of room given for decision, taking actions and to focus one’s energy;

- an appropriate difficulty to grow without being demanded too much;

- alignment about what people feel responsible for;

- alignment on how people evaluate their achievements; and

- an ongoing discussion about the conflicts stemming from not doing all of this to perfection.

Compare the list with your situation at work. What do you feel responsible for? Do you have enough room and is the difficulty appropriate? Does this align with the others around you and do you all agree about the authority for evaluating the achievements?

Adding balloons – a team’s blind spots

The agile inspect and adapt principle is a well established mechanism to improve team work and to adapt to changes. In Scrum, during the retrospectives held once every sprint, the team reflects on their collaboration and decide on improvements to be implemented in the next sprint.

However, assessing own strength and flaws is not so easy. Some teams are great at accepting major flaws because they learnt to live with them or nobody knew of a better way. Therefore, even though teams implement inspect and adapt, they still tend to stick to a somewhat flawed mode of working. The typical story of inspect and adapt is the following:

- Work as before: Team members set the initial structure up as they can envision it. Namely, they create a generally acceptable mix of how they worked before and stick to this.

- Self-assessment: There is no obvious best way of working together. Teams usually rely on their own assessment. Thusly, even ineffective modes of collaboration are acceptable when nobody knows of a better one.

- Reward for delivery: The team is rewarded for delivering a product, not for building a high-performance team. Investing into the team is thus easily put off for later. Increasing pressure on features makes this effect even stronger.

- Coupled cycles: Retrospectives are usually tied to development sprints. A team improvement iteration thus lasts one sprint. More difficult improvements drag along for three or four iterations of ineffective team work.

- Ad hoc conflict resolution: Team members do not necessarily have refined skills in conflict resolution. More difficult conflicts thus flare up ever so often and are dragged along through the development, never quite resolved.

Overall, teams tend to start with what the members can perceive as potential ways of working together – usually how they worked the last time – and then slowly do some minor improvements while developing more and more blind spots for flaws in their collaboration. Team members may even proudly point to some nifty work-around they invented to cover the flaws.

Teams used to pulling a cart with square wheels are likely to do so the next time as well. The inspect and adapt cycle allows them to e.g. attach some balloons.

Closed loops

Inspect and adapt as such promotes a closed loop principle for developing products. In a software development team, this closed loop consists of four elements:

The first element is the story team members and stakeholders share and agree upon. A story is concise and precise summary of the what the software is all about and for what purpose. This story serves as the target of the closed loop system. Such a story is much more effective when

- team members and stakeholders take responsibility to realizing it;

- everyone can assess and agree upon the current state and progress made towards realizing the story; and

- everyone relates their tasks to the story and can easily decide which tasks to prioritize and which to drop .

The second element is the external feedback loop between team, customers and users. Getting feedback from real life usually drastically changes the perception of what is important (see meet with users to create great products). This external feedback loop works much better when

- the team can quickly get feedback to new ideas, first implementations as well as to the current product;

- the feedback is reliable, i.e. it predicts the usefulness of ideas or states real issues or opportunities customers and users have; and

- the team can easily judge the importance of the feedback.

The third element is an internal feedback loop, where teams assess the quality attributes of the product itself, e.g. bugs, response times, cleanliness of code, attractiveness and more. The internal feedback loop works much better when

- the team uses a risk based approach to balance investment into manual and automated testing versus untested gaps;

- the team has prioritized targets to evaluate against; and

- building quality (as opposed to rushing to the market) is valued by stakeholders.

The fourth element is the conversation in the team and with stakeholders to figure out, what to build and what not, in what order and how. This includes a development strategy, the scope, the conceptual structure as well as making all details from processes to UI to code and tests work together. The conversation works much better when

- team and stakeholder agree upon the fundamental of how they want to work together;

- the team invests into strong team properties; and

- team and stakeholder work on the conflicts.

When looking how to improve team work, the team should therefore cast a critical glance at the story, the feedback loops and how they lead the conversation with stakeholders.

Feedback, feedback, feedback!

It should have become obvious by now: the feedback loops make the difference. A team needs feedback loops

- for the individuals in and around a team, their contribution, professional skills, expectations, career goals, behaviors and values;

- for the team and how they lead the conversation, their processes, structure, strategy, and know how

- about the social space provided by the team,

- about the product they create, its function and quality, the vision behind and priorities;

- about the team’s impact on the company; their contribution to values, assets, know how, etc.

Investment into teams

Just throwing people together does not make an effective team. It needs an investment into the team (see also Collaboration – Buy or Lease?).The investment into a team is not constant. At the beginning of team work and upon major changes (vision move, team change, other needed adaptation), a higher investment into the team is needed.

Thus, it is probably a good idea to:

- adapt the frequency of the retrospectives depending on the demand of change from the team.

- make room for team development and plan with fewer story points when a team needs to adapt to a changed situation.

- plan in some reserve for up-coming team changes. The velocity measured during stable team phases will be too high.

A bigger change in the team usually results in a significant personal change. Tasks, skills and even attitude may need to change. Take for example a situation where software team realizes that their software just has too low quality. The simple fix to assign one person to work out a solution and tell the others what to do may not really work well. Some team members might need to change their attitude towards testing, other team members might lack the skills to design easily testable code, other team members need suddenly to play an active role to set a culture of quality rather than a culture of feature creation and finally team processes change so that testing actually happens.

Such situations ask for a focused change. It is thus probably a good idea to:

- run time-boxed experiments of new modes of working where team members can get a hands-on experience of the value and the costs.

- do an intervention, where the team adopts a new way of working and makes a kick-start in acquiring the needed skills, mainly by doing it. Brief retrospectives during the intervention allow to adapt and learn. At the end of the intervention the team can decide what to adopt immediately, what later and what not at all.

Reward team building

Team members usually get little acclamation for creating a great team. Praise and blame are given for the results. Of course people in principle know, that the better the team members work together, the better the result is going to be. It is nevertheless just an indirect consequence. Thus having found a generally acceptable way of working together is good enough for most teams.

Team members have little vision of a how great team work actually is; inspect and adapt does not include external feedback, groupthink is to be expected; and nobody demands good team work.

Given these points: it is probably a good idea to

- get outside feedback by e.g. inviting other teams to the retro, or even going to other teams.

- get to know different ways of working, e.g. from other companies, related jobs and more. A software team could have a closer look at how designers, mechanical engineers or even a team of doctors collaborate.

- use moderators so the team can question already accepted rules and work procedures.

- regularly replace some team members. New team members are by nature more likely to ask the “silly” questions needed so a team starts changing stuff.

- show how you do it to the world (or some part of it). Post an article, a video, a picture, go to a conference and more. This invites discussion and insights.

Long-term investment

The amount of learning in a project is limited. In the end, the team has to deliver a product and cannot devote too much time into forming the perfect team.

Given this we need to strive for an organization where teams identify and try out new ways of working, talk about them with other teams so the successful patterns spread through the organisation.

Replacing the square wheels

Back to the initial question: how to achieve that teams do not pull a cart with square wheels any longer?

It seems quite clear, that there cannot be a silver bullet but many small improvements and loads of work.

First of all, it seems a good idea to setup a team so that team members actually collaborate.

Second, it investing into team development and set aside time for this is a must. The time needed is cannot be constant but needs to adapt.

Third, some things can profit from a focused intervention (aka flipping) where a team acquires the needed skills, processes and attitude so a change can be realized.

Fourth, teams profit when they are challenged by seeing other ways of working, new team members and moderators so they can detect their blind spots.

Fifth, Learning to collaborate well needs time! It seems that an organization needs long-term investment into team work and structures that allow spreading new and better ways of working.